Tree of Hope, Partition Museum, Amritsar

https://www.partitionmuseum.org/ (Retrieved May 7th, 2022)

“It has no other end in view than to throw light on things by tracing what is manifest back to what is hidden. It is quite satisfied if reforms make use of its findings to replace what is injurious by something which is more advantageous.”

Freud (1912)

Prologue

The first clashes between the Meitei and Kuki communities broke out on May 3, 2023. The state has been a bubbling cauldron of hatred, violence and killings claiming about 200 lives leading to the fleeing of thousands from their homes. According to data presented by Inspector General of Police (Operation) I K Muivah earlier this month, over 5,000 cases of arson have been reported, which included more than 4,700 houses that were torched and 386 religious structures have been vandalized[1].

[1] https://indianexpress.com/article/india/manipur-violence-meitei-kuki-tribe-conflict-four-months-8956725/

Introduction

The present exploration seeks to bring to bear the psychoanalytical gaze to the intra- and inter-psychic processes at play in the context of communal-ethnic-caste conflicts in an effort towards having a loving “us” without needing to have a hated “them”. It is an attempt “to replace what is injurious” as Freud puts it and contribute to moving towards better and more harmonious inter-community relations.

Antagonisms, feelings of hostility and resentment between communities are part of everyday existence in the world. Under ordinary times, they may take the shape of cracking pejorative jokes at the other community members while having tea together at the local tea shop. There are relationships and friendships among individuals across communities. Similarly, feelings of humiliation and being weak are part of an individuals’ existence but remain confined to the verbal sphere and may surface in discussions in the shape of complaints, grievances and verbal swipes at the others. Similarly, there are collective traumas with regard to historical events where there has been no healthy mourning and processing of the perceived hurts and humiliations.

In this scenario the arrival of a charismatic leader who promises to transform the group and whose strengths and qualities mesh with the emotional needs of the group, impacts the turn of events.

A charismatic leader who shores up the group identity and esteem by hurting and destroying another group, stokes feeling of humiliations, feeds into insecurities and anxieties and escalates tensions among the groups. As the communal temperature rises, a person loses or seizes to have an individual identity and is seen totally as a member of the ‘enemy’ group. Thus ‘A’ is seen as a ‘Muslim’; B is seen as a ‘Hindu’; “C is seen as a Sikh; “D” is seen as a Christian”. The charismatic leader escalates tensions to a boiling point of volcanic eruption. The ‘other-enemy’ community becomes the repository of all that is bad and demonized and referred to and reduced to “vermin” or “cockroaches” or non-human “beast-like creatures”. Killing such creatures does not induce guilt like the killing of a human being. The paper explores possibilities of healthy mourning and processing of trauma associated with historical events to move towards diminishing the possibilities of malignant use.

The Holocaust during World War II is an illustration of perhaps one of the most extreme examples of the ‘othering’ of a community and a determined bid towards its extermination. The ideology, best exemplified by Nazism, postulated the white Nordic Aryan as a ‘master’ race with Jews and blacks as inferior. The ideology was implemented in Germany by the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (the National Sozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei, commonly referred to as the Nazi Party) found its fullest expression under the leadership of Adolf Hitler who led the party from 1933 until his death in 1945. Jews in Germany were systematically deprived of their property and livelihoods as the Nazis brought in laws between 1933 and 1939 to marginalize and disenfranchise Jewish citizens and proceeded to exclude them from professions and commercial life. A decree was passed prohibiting Jews from using public transportation. Jews over the age of six were made by law to mark themselves by wearing the yellow Jewish Star on their outermost garment. Regulations forced Jews to live in designated areas of German cities.[1] The culmination of the “othering” process was the deportation to concentration camps and labour camps, and death in gas chambers.

What could be the underlying factors that prompted and enabled this horrific process? The less unsettling option is the belief that it was some unfortunate predisposition in the German character that made Nazism and the Holocaust possible. In addition to the propaganda of the victors of the war and liberators of those held in concentration camps, a large number of films, novels and comics conveyed the idea that the Germans were ‘evil’. Koonz (1987) offers us pointers: “Still, underneath the unique and dated style of Nazism lurked a more universal appeal – the longing to return to simpler times, to restore lost values, to join a moral crusade. What needs drove those millions of “good Germans” willingly into dictatorship, war and genocide?” (p. 18).

Today, with the global rise of cultural nationalism in several countries the view that the processes which led to the Holocaust were specific to German society in the 1930s is less comforting or even plausible. Freud (1930[1929]) speaking of aggression in humans seems prescient in the context of the decrees seizing the property of Jews and the concentration camps that were to follow, observes: “As a result, their neighbour is for them not only a potential helper or sexual object, but also someone who tempts them to satisfy their aggressiveness on him, to exploit his capacity for work without compensation, to use him sexually without his consent, to seize his possessions, to humiliate him, to cause him pain, to torture and to kill him.”(Emphasis added). (p. 111).

Arendt (1951), German-American political theorist who has examined totalitariansm and authoritarianism articulates the need for engagement with drives to violence and power and observes, “Yet to turn our backs on the destructive forces of the century is of little avail”. (Preface).

Psychoanalysis and social phenomena

The contribution of psychoanalysis to an understanding of the individual psyche is vital and invaluable. The present attempt is in the nature of going to Sigmund Freud’s ‘Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego’ and ‘Civilization and its discontents’, taking it forward and bringing to bear psychoanalytical approach to social issues. Freud (1930[1929]) in the context of the ‘us’ and ‘them’ perceptively observes “It is always possible to bind together a considerable number of people in love, so long as there are other people left over to receive the manifestations of their aggressiveness.” (p. 114).

Klaus Von Dohnanyi, the Mayor of Hamburg at the opening ceremony of the 134th International Psychoanalytical Association in 1985 at Hamburg pointed out that the International Psychoanalytical Congress held in Wiesbaden in 1932 – “hardly appears to have been aware of the imminent threat posed by National Socialism which, only a few months later, set up in Germany the most brutal dictatorship in human memory” and brought about untold misery and suffering in the world. Mitscherlich, (1971) the German psychoanalyst urged an expanding of horizons and participation in research on collective behaviour of groups otherwise psychoanalysts “will have manoeuvred [themselves] into an isolation of [their] own making.”(p. 164).

My own perspectives on these issues have evolved through almost four decades of engagement with movements for social change, which though attempting to move towards a better society, showed a marked reluctance to take on board psychological dimensions of social problems. Jacques (1955) offers clues as to the arduous road to social change when he writes: “From the point of view here elaborated changes in social relationships and procedures call for a restructuring of relationships at the fantasy level, with a consequent demand upon individuals to accept and tolerate changes in their existing patterns of defences against psychotic anxiety. Effective social change is likely to require analysis of the common anxieties and unconscious collusions underlying the social defences determining phantasy social relationships”. (p. 498).

Scope of the paper

This paper seeks to explore and thereby extend possibilities of psychoanalytical insights with regard to intra- and inter-psychic processes being able to constructively contribute towards understanding the phenomenon of ‘othering’ and moving towards better inter-community relations in India. I use ‘community’ in the sense that Volkan (2013), who as a psychoanalyst has worked for peaceful co-existence of diverse communities in major conflict areas of the world, uses the term ‘large group’ referring to persons who share a feeling of sameness and may number in thousands and millions. The identity may be based on markers in the nature of religion, caste, ethnicity, class, language and geographical region amongst others. Volkan (ibid) illustrates the notion by articulations such as: “we are Apaches; we are Lithuanian Jews, we are Kurdish; we are Slav; we are Sunni Muslims; we are Taliban brothers; we are communists.” (Pg. 210). In India, the identity could be religious, whether Hindu, Christian or Muslim; caste, whether Dalit, Other Backward Castes (OBC) or Brahmin; Adivasi, whether Gond or Thangkul. These identities represent a pulling together of diverse threads including shared myths, realities and histories amongst a host of cultural and political factors.

In phenomena like war, xenophobia, fascism, communalism and genocide -social, economic, political, cultural and psychological factors play a significant role. Akin to the angles of a prism which reveal behind the ‘manifest’ apparent white light the ‘hidden colours’, the psychoanalytical perspective is not offered as the single factor explanation, but one of many views of looking at social phenomena. Jost et al (2003) based on their research in twelve countries in the context of political conservatism posit that given the complexity of human belief systems a complete explanation is unlikely and that: “The most that can be expected of a general psychological analysis is for it to partially explain the core of political conservatism because the peripheral aspects are by definition highly protean and driven by historically changing, local contexts.” (p. 369).

Family constellation

The inculcation of a deep reverence for the mother and father is through a number of folk and mythological stories. According to a popular myth, a competition was announced that whichever god circled the universe fastest would be worshipped first. Ganesha, whose vahan (carrier) is a mouse had no chance of winning, given gods who had creatures like tigers and eagles as carriers. Ganesha promptly circled his mother and father Shiva and Parvati, representing the whole universe and won the race.

Manifestly, there is utter denial of any ambivalence in the mother-son dyad routinely reflected in Hindi cinema. One of the most famous dialogues of Hindi cinema in a sibling exchange as to respective achievements in life is “mere paas maa hai” (trans. I have mother). However, the films of even progressive male directors reflect the denial of ambivalence. A film screened at the film festival on ‘Gender and Sexuality’ (International Festival on Gender and Sexuality – Identities and Spaces: 12-15 May 2007) in Delhi titled “All About Our Mothers” (Directed by Manak Matiyani and Kuber Sharma, India) is illustrative. The documentary is a portrait of the mothers of the two young male directors. The film brings up issues of house-work, role expectations from women, the double burden of working outside and inside the house, but the context/paradigm of the film is exclusively husband-wife relations. It is standard practice in India for a mother to wash the clothes including the undergarments of the sons till marriage when the chore is taken over by the wife. It is implicit that the son old enough to make films will get cooked food on the table and washed underpants. The film has a romanticised portrayal of the “mother-son” relation without a hint of ambivalence, conflict or resentment. The sons are paying a tribute to their mothers and making them “heroines” and the mothers are helping the sons in making the film that eulogises their role as mothers.

Films and popular media aside, the stories on which a child grows up emphasize the utter selflessness of the mother and total concern for the son with an underlying subtext of potential betrayal or doubt regarding the loyalty of the son, after marriage. “Joru ka gulam” (trans. “Slave-of-the-wife”) is one of the commonest sayings to sons who have got married. The implication in the saying is neglect of the mother after marriage.

Splitting, Projection, Integration

According to traditional Freudian psychoanalysis with regard to stages of development, the child initially does not have the notion of a separate existence from the mother in the first few months of existence. The baby perceives experiences as pleasant or unpleasant, but does not realize that it is the same entity that is experiencing both the satisfying and the frustrating experiences.

The baby is not aware that the fed-admired-secure baby is the same individual as the hungry-rejected-scared baby. At about the age of 36 months the integration is estimated to take place in the baby that it is the same individual who experiences pleasure and frustration. The baby develops a realistic picture of himself or herself – that he is not entirely ‘good’ and kind nor entirely ‘bad’ and cruel. This in turn helps the baby in perceiving other people as integrated individuals too. The baby also develops a more realistic picture of the mother – that the loving mother and the frustrating mother is the same person. The un-integrated bad parts are dealt with unconsciously through repression or externalization that is deposited in things or animals or people outside oneself.

According to Kernberg the normal self is a comprehensive whole and represents an integration of contradictory “all good” and “all bad” libidinally invested early self-images. This normal self relates to integrated object representations which have incorporated the “good” and “bad” primitive object representations. Kernberg observes “Therefore, although normal narcissism reflects the libidinal investment of the self, the self actually constitutes a structure that integrates libidinally invested and aggressively invested components; in simple terms, integration of good and bad self-images into a realistic self-concept that incorporates rather than dissociates the various component self-representations is a requisite for the libidinal investment of a normal self. This also explains the paradox that integration of love and hatred is a prerequisite for the capacity for normal love.”(P. 316).

Kernberg speaking of normal and pathological narcissism posits that the lack of integrated self generally co-exists with lack of integration of object representations which are caricatures of “all good” and “all bad”. This results in diminished capacity for empathy or for realistic judgment of others, in depth and “behaviour is regulated by immediate perceptions rather than by an ongoing, consistent, internalized model of others, which ordinarily would be available to the self.” (P. 317).

In the context of ethno-religious-caste-community tensions, there seems to be universality of the “enemy” other being invariably “dirty” for the dominant community. In rising Nazi Germany – Jews were categorized as ‘dirty’; in the context of Hindu-Muslim tensions – Muslims are seen as ‘dirty’ by Hindus and in the colonial paradigm the colonial masters designated the natives as ‘dirty’. This lack of integration is not confined to feelings of ‘dirtiness’ alone, but extends to other ‘bad’ qualities like lust.

The across-the-board prevalence of these dynamics in the context of inter-community tensions and violence raises doubts as to the smooth integration of the “good” and the “bad” in the self-posited in traditional psychoanalytical theory. Perhaps, it is a continuing process at variance with the conception of the integrated ‘normal’ self by the age of about three years. Volkan (1986) refers to the integrating as ‘mending’ and observes “It is my belief (1985a, b) that this integration—which I like to call mending—as well as the repression of the “unmended” units, is never completed, so it is possible for object relations conflict to continue.”(Pg. 184).

We see a persistent and continuing resistance to acknowledging the ‘bad’, the ‘dirty’, the ‘lustful’ at an individual as well as the collective community level. Perhaps, the sense of being ‘good’ or possibly ‘good enough’ is fragile and gets destabilized and threatened by an acknowledgement of the ‘bad’ in the self. The ‘bad’ is therefore externalized to outside objects, gets condensed with projection later and may contain devalued aspects of parents. Volkan (1986) posits that “Such “bad” suitable targets contain the precursors of the concept of an enemy shared by the group.” (p. 185). In a parallel process some objects, animals or people become the reservoirs of the ‘good’ aspects of the self the idealized parts of the parents. For example, to a growing boy in a Hindu household the cow may become a reservoir of the nurturing, milk feeding and protective mother. In Finland, it may be a sauna which may represent the soothing – idealized mother for the child. Often familiar foods and cultural practices become suitable targets for the externalization of the good aspects. In times of perceived ‘threat’ or sense of humiliation these get amplified and, in a sense, louder.

Enemy as reservoirs and narcissism of minor differences

In osmosis like process the growing child imbibes stereotypes, biases and prejudices prevalent in the community. The mothering or care-taking person helps select durable targets for externalization who become the shared reservoir of the ‘bad’ parts. Thus for a Muslim child a ‘pig’ (the consumption of which is considered ‘haraam’ or prohibited in Islam) may be a repository of all ‘dirtiness’. A Hindu child growing amidst escalating communal tensions may have the ‘Muslim’ as the repository of all ‘dirt’. The target and reservoir of the un-wanted is often ‘dirty’ and ‘smelly’ taking on the characteristics of faeces as the child is taught that excreta are dirty. The objects are shared reservoirs for the community. The thought that the other may be like us is intolerable and unacceptable and minor differences acquire a magnitude totally disproportionate to the at times, trivial differences between the two communities.

Freud used the term phrase narcissism of minor differences first in “The Taboo of Virginity” (1918): “… each individual is separated from others by a “taboo of personal isolation”, and … it is precisely the minor differences in people who are otherwise alike that form the basis of feelings of strangeness and hostility between them. It would be tempting to pursue this idea and to derive from this “narcissism of minor differences” the hostility which in every human relation we see fighting successfully against feelings of fellowship and overpowering the commandment that all men should love one another.”(p. 199)

Freud (1930) writing of minor differences observes: “It is clearly not easy for men to give up the satisfaction of this inclination to aggression. They do not feel comfortable without it…. it is precisely communities with adjoining territories and related to each other in other ways as well, who are engaged in constant feuds and in ridiculing each other — like the Spaniards and the Portuguese, for instance, the North Germans and South Germans, the English and Scotch, and so on. I gave this phenomenon the name of “the narcissism of minor differences,” a name which does not do much to explain it. We can now see that it is a convenient and relatively harmless satisfaction of the inclination to aggression, by means of which cohesion between the members of the community is made easier.” [p. 114].

Relatively harmless to killer rage

The role of the narcissism of minor differences, which at the time was thought of as “relatively harmless satisfaction of the inclination to aggression” by Freud, possibly needs to be explored further in the context of ethnic-religious – national tensions and strife. Many times, an outsider cannot easily distinguish the two conflicting communities whether it may be Gujarati Muslims and Gujarati Hindus or Hutus and Tutsis. Volkan (1986) observes: “In the villages, where usual masculine dress consists of baggy trousers and shirts, the Greeks wear black sashes, the Turks red. In “normal times” a breach of this colour code might be tolerated, but when ethnic relations are strained, when group cohesion (and therefore individual integrity) is threatened, a Turk would rather die than wear a black sash, and a Greek would be just as adamant in his refusal to wear a red one.”(pg. 181).

In times of tensions based on any of the indicia in the nature of race, caste, religion – the Community A feels it does not have any similarities with the ‘other’ Community B and focuses upon and magnifies the minor differences that are bound to exist. Kakar in his work ‘Colours of Violence’ illustrates the process of emphasizing the minor differences, imbuing them with heavy emotional content to widen the schism and chasm out and quotes a speech of self-styled Hindu monk Sadhvi Rithambara: “The Hindu writes from the left to right, the Muslim from right to left. The Hindu prays to the rising sun, the Muslim faces the setting sun while praying. If the Hindu eats with the right hand, the Muslim eats with the left. If the Hindu calls India “mother”, she becomes a witch for the Muslim. The Hindu worships the cow, the Muslim attains paradise by eating beef. The Hindu wears a moustache; the Muslim always shaves the upper lip.” (p. 165).

Volkan (1986) observes: “So we focus on minor differences, or we create them, in order to strengthen the psychological gap between the enemy and ourselves. The strengthening of the psychological gap is unconsciously obligatory since it serves as a buffer to keep a group’s unwanted parts, impulses, and thoughts—which originally belonged to it— from coming back into the group’s self.”(pg. 187).

Inter-se co-operation between members plays a role in the evolution of successful species. This may be particularly true in the case of human beings who lack horns or claws or other features of attack and defence. Erikson speculated that the human species started using the skins, feathers or claws of other animals to protect the defenceless naked body. That on the basis of the specific devices chosen, each tribe, clan or group developed a sense of shared identity and a belief that it alone constituted the human species. Erikson (1966) observed that “Man has evolved (by whatever kind of evolution and for whatever adaptive reasons) in pseudo species, i.e., tribes, clans, classes, etc., which behave as if they were separate species, created at the beginning of time by supernatural intent.”(p.606). In an effort to understand killings amongst the human species, Volkan (2009) taking Erikson’s ideas forward speculates that possibly if large groups felt they belonged to different species, they would kill each other.

Historical and Intergenerational Trauma

“We never wanted to burden them with our memories. Jo humharadukhtha who hamaretak hi rehta, we wanted the sadness to end with us, to remain in our generation, to never be passed down.”

Malhotra, (2022) – Pg 21

Historical trauma refers to distressful experiences or events which occurred in the past impacting a group or community. Unlike trauma which impacts an individual the traumatic events are +suffered by a collective. The infliction of trauma on the group may be based on factors like the religion, ethnicity, caste, sexual orientation or nationality of the collective. Inter-generation trauma refers to trauma which gets passed down from those who lived through the experiences to the succeeding generations.

The Holocaust, the partition of India, the trauma of the forcible taking away of children of indigenous peoples of Canada into government residential schools[2] or the trauma of the caste system which Dalits have endured in India are examples of historical trauma and intergenerational trauma. Children of holocaust survivors were the first group in which the impact of the trauma on subsequent generations was studied. Rosenkranz, Holocaust Program – Group Facilitator (2015) observes “In spite of the fact that many survivors chose to remain silent about their experiences, the trauma was ever present; “It loomed in the air we breathed, like second hand smoke,” stated a sixty two year old physician and son of survivors.”(pg.3). In a similar vein Malhotra (ibid) quotes Indian-Canadian author-actor Lisa Ray whose grandfather and father came to West Bengal at the time of partition in 1947 “What I feel about Partition, even though I haven’t lived through it, is real. It’s very, very real.” (pg. xxix).

In the context of the inter-generational trauma of caste, Yengde (2019) speaking of the film India Untouched by K.Stalin documenting Dalit girl students being forced to clean the premises and bathroom of the schoolwrites: “As I am walking, the mind is stunted and I am constantly thinking about the repeated assaults on Dalit minds that force them to inferiorize their being.”(pg.42). In the context of the revolutionary poet Pash’sline – “sabse khatarnak hota hai hamare sapno ka mar jana” (trans. The most dangerous is the death of our dreams),Yengde observes that along with the humiliations and deprivations suffered, the capacity and nature of dreaming gets impacted by the caste system – “Dalit middle-class dreams are yet to mature; for now they exist in the mimicry of the oppressor Other.”

Invocation of past trauma

The slogan “garv se kaho hum hindu hain” (trans. “Say with pride we are Hindu”), struck a chord among a significant number of Hindus, gained much traction and played an important role in mobilizing, perhaps pointing to a continuing sense of humiliation and shame from historical events which occurred hundreds of years earlier. Malhotra (ibid) based on a number of interviews across generations of partition survivors observes “that the intensity with which descendants described inherited stories seemed as visceral” and writes “Their second hand connections to these lived traumas and histories went well beyond surface telling into something which has become intrinsically theirs.” (pg. xxii).

A leader can strike the right chords which awaken and resonate with buried feelings of guilt and emasculation from an event from the past, charismatically bind individuals and catalyze a group to a call for action and revenge for the humiliation of their forefathers through attacking and destroying the “other” group seamlessly conflated with the old attackers of the past. The Somnath temple in the state of Gujarat, India was looted and destroyed in 1025 A.D. by Mahmud of Ghazni. The mythic hero of the epic Ramayana Lord Rama was supposed to have been born in Ayodhya in the state of Uttar Pradesh. It is a common belief that a temple was built on the spot where was Ram was born which was destroyed and a mosque built by the Mughal emperor Babar in 1528-1529 referred to as Babri Masjid. In 1992 invoking the dual trauma, Lal Krishna Advani, the then Leader of Opposition in the Indian Parliament started the Ramjanambhoomi Yatra (Journey to reclaim the birth place of Lord Rama) from Somnath and culminating in the destruction of the Babri Masjid. The Indian Muslims of today became the attacking Mongol hordes of the medieval times as well as the progeny of Babar responsible for destruction of the Ram temple. The invocation by Mr. Advani of the traumatic events evoked strong emotions with an intensity, as if the looting of Somnath and the alleged destruction of the Rama temple had happened a day before and the participants in and along the Yatra route were present and saw these long past events themselves, to use an evocative colloquial phrase“khudapniankhon se dekha” (trans. ‘saw with my own eyes’).

Volkan (1997) describes the invocation by Slobodan Milosevic of the Serbian defeat in Battle of Kosovo in June 1389 by the Ottoman Empire to stoke ethnic tensions and uses the term ‘time-collapse’ “where people may intellectually separate the past event from the present one, but emotionally the two events are merged.” The Bosnian Muslims of today became the Ottoman Turks – the ‘enemy’ in the chosen trauma of Bosnian Serbs, akin to the conflation of the Indian Muslims with the attacking Mongol hordes in 1025 and the destroyers of the Ram Mandir (Temple) in 1528-1529.

Mourning and memory

“Mourning is regularly the reaction to the loss of a loved person, or to the loss of some abstraction which has taken the place of one, such as one’s country, liberty, an ideal, and so on.”

Freud (1917)

Mourning is a process of grieving for loss and coming to terms with the death of someone precious to us. Events like the partition of Indian into two countriesin 1947 or the abrogation in 2019 of Article 370 of the Constitution of India which granted special status to the State of Jammu & Kashmir can also evoke feelings of loss in an individual. Mourning helps in coming to terms with the pain and trauma of loss and in that sense can be looked upon as “healthy mourning” rather than pathology. In contrast, melancholia was recognized as a distinct disorder termed “melancholic depression” and is now looked upon as a species of the broad category of major depressive disorders. It is qualitatively different from the term depression as used in ordinary parlance and is characterized by chronic feelings of sadness, lack of interest in anything and may impact performing daily activities like getting up and brushing teeth.

Lack of healthy mourning may take us towards melancholia. Freud(1917) enumerating the characteristics of melancholia and mourning as “profoundly painful dejection, cessation of interest in the outside world, loss of the capacity to love, inhibition of all activity, and a lowering of the self-regarding feelings to a degree that finds utterance in self-reproaches and self-revilings, and culminates in a delusional expectation of punishment” and postulates that “The disturbance of self-regard is absent in mourning; but otherwise the features are the same.” (pgs. 243-244).

Possibly, lack of healthy mourning in the context of historical traumatic may induce feelings of smallness, guilt and shame at a collective level in a community. There were a number of invasions of India in the medieval period. Mahmud of Ghazni invaded India a number of times from 1010 AD onwards and destroyed and looted the Somnath Temple in Western India. Perhaps, not being able to protect Mother India – Bharat Mata – from the lootings, destructions and killings by attackers from medieval times over the years engendered a sense of shame in the Hindu psyche. Bacchetta (2004) writes “As Andrew Parker et al. [1992 have amply demonstrated, in so many nationalisms across the globe the territorial component is associated with, or symbolised as, a chaste female body, often a mother or motherly figure. The notion of her potential violation by foreign invaders is also widespread” (p. 27).

These feelings may at times be evoked by a leader to bind together a community and seek revenge attacking another group conflated with the enemies of the past and restoring pride as a collective.The leader aided by ‘transference’ may tap into the processes of the unconscious to mobilize the masses. In the context of the role of the charismatic leader, Fromm (1982) points towards an avenue to explore, “The transference phenomenon, namely the voluntary dependence of a person on other persons in authority, a situation in which a person feels helpless, in need of a leader of stronger authority, ready to submit to this authority, is one of the most frequent and most important phenomena in social life, quite beyond the individual family and analytical situation. Anybody who is willing to see can discover the tremendous role that transference plays socially, politically and in religious life.” (p.41). Picking up moments of triumph from historical events – termed “chosen glory” by Volkan (2013) does not seem to work as well to restore a sense of pride of the group.

Processing injury and loss

Freud (1917 [1915]) speaking of the process of mourning observes “Each single one of the memories and expectations in which the libido is bound to the object is brought up and hyper-cathected and detachment of the libido is accomplished in respect of it. Why this compromise with the command of reality is carried out piecemeal should be so extraordinarily painful is not at all easy to explain in terms of economics. It is remarkable that this painful unpleasure is taken as a matter of course by us. The fact, is however, when the work of mourning is completed the ego becomes free and uninhibited again.”(p.245).

In the context of the Vietnam War Memorial in Washington as an expression of mourning for the loss of American lives in the Vietnam War, Volkan, V (1997) illustrates the process of mourning with regard to large traumatic events and quotes Volkan, K (1992) senior editor in the Middle East Times: “As a reflection of death the memorial allows the living to fuse with the dead, through sight and touch. As a reflection of the psychodynamics of mourning, Lin’s creativity resulted in a ritual that is soothing in itself; visitors symbolically repeat the mourning process, and thus master it, every time they come and go, touch the stone and leave.”

The visitors read the names the dead with the granite walls reflecting their own image and can use pencil and paper to get a silhouette of the name and take is as a concrete material remembrance evoking memories, associations and feelings . Malhotra, 2018 writes “This was the first time that the importance of material memory truly dawned on me- the ability of an object or possession to retain memory and act as a stimulus for recollection.” (pg. 4).

Partition Museum, Amritsar in India

The Partition Museum in Amritsar, in the Indian side of Punjab, was opened in August 2017 to remember all those millions who lost their homes or loved ones at the time India was divided into the two separate entities of India and Pakistan in 1947.

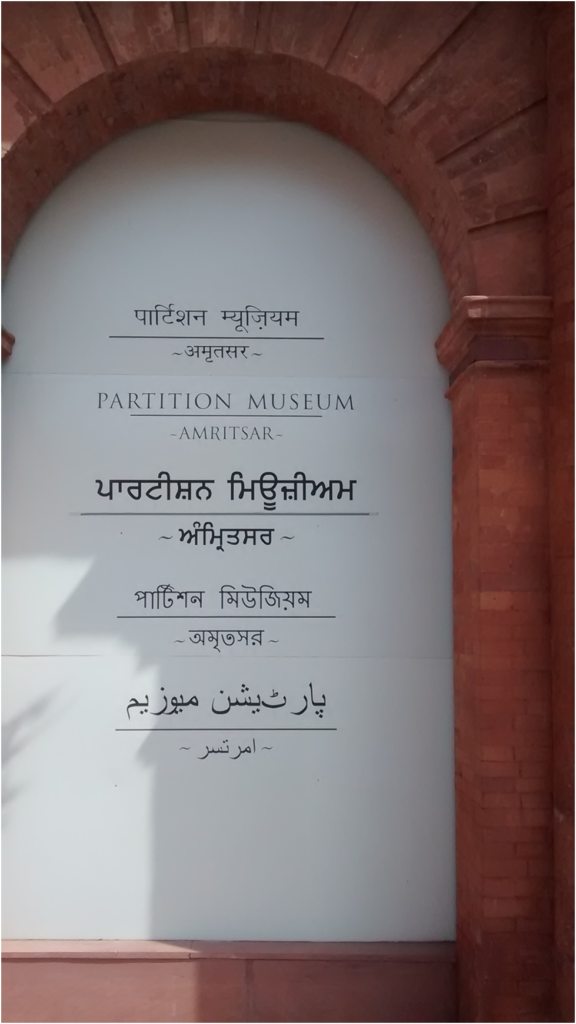

Figure 1 is the marble plaque at the entrance of the Partition Museum with the title ‘Partition Museum, Amritsar’ inscribed in Hindi, English, Gurmukhi (Script in which Punjabi written in India), Bengali and Urdu the languages spoken by the communities which were primarily impacted by the Partition.

Figure 1 – Partition Museum, Amritsar, India

(Photograph by Rakesh Shukla)

It is a pioneering attempt as part of the process of acknowledging and initiating the process of mourning with regard to the feelings of loss and trauma.

The Partition Museum is conceptualized as a People’s Museum and thousands of people who have shared their histories and artefacts. The Museum has oral histories, soundscape in each gallery, original artefacts donated by refugees, newspapers, magazines and photographs showing the migration and camps, letters written by refugees, government documents as well as art installations.

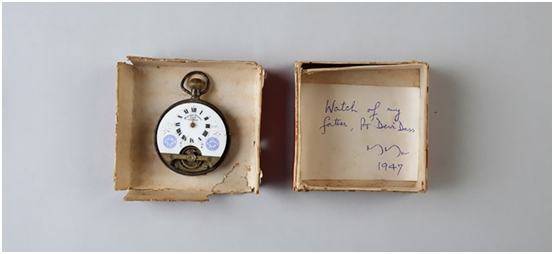

Pandit Devi Dass of Nowshera, Pakistan got separated from family during partition and there was no news as to his fate. An acquaintance during the course of helping the mass cremation of unclaimed bodies recognized the body of Pt. Devi Das and removed the watch and asked the family members to contact him. The watch was donated by the son to the Partition Museum.

Figure 2 – Watch of Pt. Devi Dass of Nowshera, Pakistan – Partition Museum, Amritsar.

https://www.partitionmuseum.org/ (Retrieved May 7th, 2022)

The spectacles in Figure 3 belonged to the father of Amol Shome who was from Mymensingh, East Pakistan and now Banglasesh. The family migrated to India in 1951 and donated the spectacles to the Partition Museum.

Figure 3- Spectacles 1934 donated Amol Shome belonged to his father. Partitaion Museum, Amritsar.

https://www.partitionmuseum.org/ (Retrieved May 7th, 2022)

Malhotra, (ibid) talks about two objects a metallic vessel – ghara and a yardstick – gaz – which had travelled from Lahore to Amritsar and then Delhi in her family and writes “And when they were picked up, grazed, studied, remembered and situated in anecdotes of a time gone by, they proved to be the most effortless yet effective stimulus for extracting memory”. (pg.4)[3].

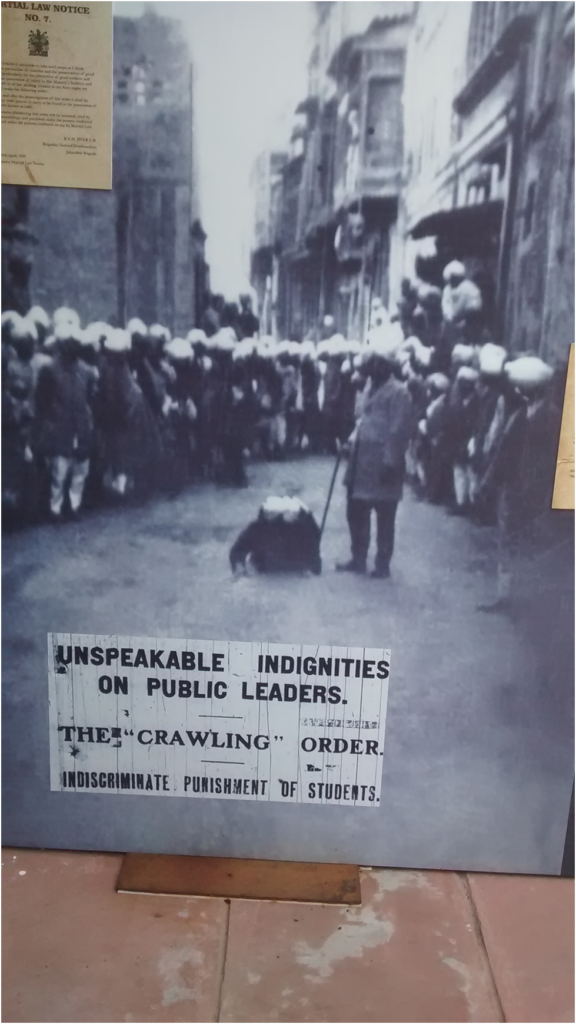

The “Crawling Order” was promulgated on 19th April, 1919 by Genenral Reginald Dyer required all those who passed through the lane in Amritsar to do so ‘on all fours’. A flogging post was set up in the middle of the lane, on which soldiers punished anyone, who disobeyed, with lashes. After that the lane came to be known as “Korian – wali Gali”, the Lane of Lashes.

Figure 4- Martial Law Notice No. 7, Partition Museum, Amritsar.

(Photograph by Rakesh Shukla)

The emotionally moving journey through the museum culminates at the “Tree of Hope” in the last gallery. Visitors can articulate their feelings and thoughts evoked and inscribe them on green leaves adorning the Tree of Hope.

The Museum ends with the Gallery of Hope where the visitor can write a message on the Tree of Hope and symbolically green the tree.

Group processes

In individual therapy, awareness of unconscious intra-psychic processes of splitting and projection is used to help a person acknowledge and accept the disowned split ‘bad’ parts and take back the projections on to ‘other’ figures.

It would be constructive to initiate group processes of accessing, acknowledging and articulating the emotions aroused by the ‘bad’ parts, thus making them more manageable. This effort is essential to help moving towards accepting, owning up and learning to take responsibility at a collective level and take back projections made on to the ‘other’ community. Some of the key components of the process to move towards better inter-community relations are: developing and fine tuning the process of the application of psychoanalytical tools to group dynamics; applying the understandings of the play of intra-psychic and inter-psychic processes; developing tools and strategies to initiate group processes towards acceptance of the good and bad aspects of itself by a community. This could in the longer-term enable a shift to a healthier middle state instead of extreme swings between the ‘good’ and the ‘bad’, between ‘idealization’ and ‘persecution’ both at an individual and collective level.

References:

Arendt, Hannah. 1951. The Origins of Totalitarianism. Penguin Modern Classics.

Bacchetta, P.(2004). Gender in the Hindu Nation, RSS women as ideologues. New Delhi: Women Unlimited (an associate of Kali for Women).

Dohnanyi, Klaus Von, Mayor of the Free and Hanseactic City of Hamburg. Opening Ceremony: 34th IPA Congress, Hamburg, 1985 on Sunday 28 July 1985. 1986). International Journal of Psycho-Analysis. 67:3-8

Freud, S. (1912). On the universal tendency to debasement in love. Standard Edition, XI.

Freud, S. (1917[1915]). Mourning and melancholia. Standard Edition,

Freud S. 1921. Group psychology and the analysis of the ego. Standard Edition XVIII.

Freud S. (1930[1929]). Civilization and its Discontents. Standard Edition XXI.

Jacques, Elliot. 1955. Social systems as defence against persecutory and depressive anxiety: a contribution to the psycho-analytical study of social processes. In M. Klein, P. Heimann and R. Money-Kyrle (eds) New Directions in Psycho-Analysis. London: Tavistock, 1955.

Jost John T., Glaser Jack, Kruglanski, Arie W and Sulloway, Frank J. – ‘Political Conservatism as Motivated Social Cognition’, Psychological Bulletin 2003, Vol. 129, No. 3, 339–375

Kakar, Sudhir. 1995. The Colours of Violence. Viking, Penguin Books India.

Kernberg, Otto. Borderline Conditions and Pathological Narcissism. The Masterwork Series. file:///E:/Psychoanalysis%202/Books/(The%20Master%20Work%20Series)%20Otto%20F.%20Kernberg%20-%20Borderline%20Conditions%20and%20Pathological%20Narcissism-Jason%20Aronson,%20Inc.%20(2000).pdf

Koonz, Claudia. 1987. Mothers in the Fatherland. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Malhotra, A. 2018. Remnants of a Separation – A History of the partition through material memory. HarperCollins Publishers India.

Malhotra, A. 2022. In the language of remembering – the Inheritance of partition. HarperCollins Publishers India.

Mitscherlich,A. 1971. Psychoanalysis and Aggression in Large Groups. Int. J. Psycho-Anal. (1971) 52, 161

Parker, A. et al. (eds). (1992). Nationalisms and sexualities. New York: Routledge.

Pash, A.S.S. Sabse khatarnak kya hota hai.

https://ncert.nic.in/textbook/pdf/khar119.pdf (Retrieved 8th June 2022)

Rosencranz, M.S. Halina (2015). Group Work with Holocaust Survivors and Descendants (claimscon.org) . Retrieved 16 June 2022.

Stalin.K. 2007. India Untouched – Stories of a People Apart. Documentary Film.

Volkan,V. 1986. The narcissim of minor differences in the psychological gap between nations. Psychoanalytic Inquiry. 1986/01 Vol. 6 Iss 2

Volkan, V. 1997. Bloodlines – From Ethnic Pride to Ethnic Terrorism. Westview Press.

Volkan,V.2009. Large Group Identity, International Relations and Psychoanalysis. International Forum of Psychoanalysis, 18(4):206-213.

Volkan,V. 2013. Large Group-Psychology in its Own Right: Large Group Identity & Peace Making. (2013). In. J. Appl. Psychanal. Stud. (10)(3): 210-246.

Yengde, S. 2019. Penguin-Viking – An imprint of Penguin Random House.

[1]Laws and Decrees Timeline Layer. United States Holocaust Museum.

https://www.ushmm.org/m/pdfs/20180228_3_Laws_and_Decrees_Timeline.pptx.pdf. Retrieved 23/03/2022.

[2]1867, Canada instituted a policy of Aboriginal assimilation designed to transform communities from “savage” to “civilized”. Canadian law forced Aboriginal parents under threat of prosecution to send their children to the schools.

Retrieved 6.16.2022

[3] For a digital repository of material culture from the Indian subcontinent see: https://museumofmaterialmemory.com/

Thought provoking, in times that need thought to be provoked.